What did he do?

He was

the first investigator who carried out research designed to test whether

astrology is true according to good scientific standards, being a professional

statistician.

First

of all, he tested well defined samples of people (e.g. the Biographical Index

of members of the Academy of Medicine, 1939) in order to exclude selection bias

and ensured that they were sufficiently large to achieve statistical

significance i.e. so that the probability that any findings would be very

unlikely to be due to chance.

Secondly,

he adjusted his findings for a number of confounding factors e.g. that more

children are born at night than in the afternoon and that the time that a sign

of the zodiac is at the horizon in the East (which corresponds to an important

factor in astrology i.e. the rising sign or Ascendant differs according to the

sign.

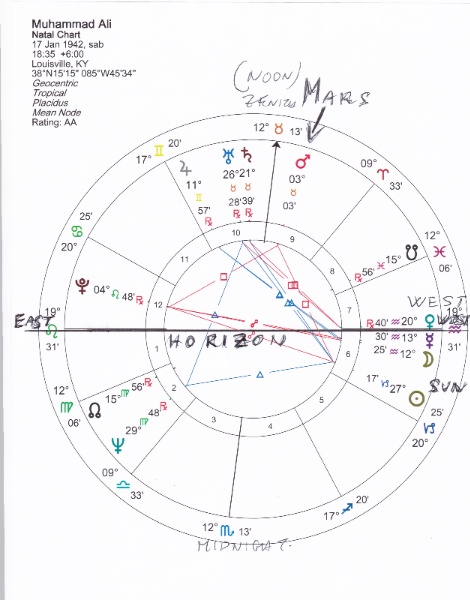

He

drew up the natal chart related to each birth duly noting the positions

of the sun signs, the houses and the planets on a circle with a horizontal

axis representing the horizon: the top half of the circle represents the

sky during the day, the bottom half the sky during the night, with the left

extremity of the horizontal axis corresponding to the East where the sun rises

and the right extremity corresponding to the West where the sun sets.

Below you can see an example of a natal chart, the one

of Muhammad Ali (Cassius Clay), a famous boxer.

You will notice that he was born at 06:35 PM, shortly after the sun had

set in the West.

Gauquelin

assessed differences in terms of all the main astrological factors that make up

a natal chart namely:

-

Signs of the zodiac

-

The Houses (according

to astrological tradition the sky is subdivided into 12 equal parts, starting

from the Ascendant which indicates house no 1; each house corresponds to a

domain of life, such as career, family, children, health, ect)

-

The Position of the

planets

-

The aspects i.e. the

relative position of one planet versus another

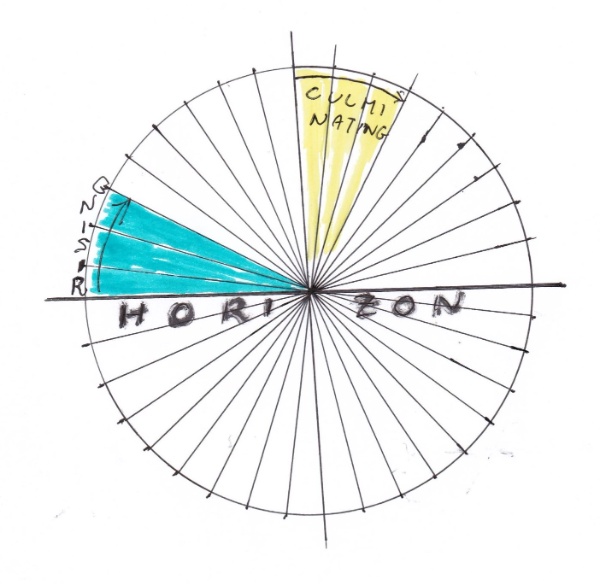

In order to assess potential differences in the

position of the planets he subdivided the circle into 36 equal sectors obtaining

a circle that resembled a roulette wheel.

He then allocated the position of the planets in each chart to one of

them. In this way he obtained

distribution frequencies related to each planet and could see whether the

distributions throughout the circle were homogenous or not. In the event of deviations, he calculated the

probability that they were due to chance alone.

His

“roulette wheel” is shown below.

At

first he assessed the charts only of Frenchmen.

This was feasible since at that time anyone could has for the birth

certificate of anyone else and the French certificate included the birth time.

After

his first findings related to profession were published one of the main

criticisms was that his data was related only to French births. He therefore decided to collect cases from

other countries as well. Unfortunately,

he discovered that birthtimes in America were unreliable, that birth

certificates do not provide birth time (UK, Ireland), that there were no birth

registries (Scandinavia) or that the authorities were not willing to provide

access (Eastern Europe and Spain). That

left few countries for his investigations, which in the end included 27,000

birth records: 12,000 from France,

7,000 from Italy, 3,000 from Germany, 3,000 from Belgium and 2,000 from

Holland. The selection was always

related to well defined groups of professionals, such as the Index mentioned

earlier.